by Stith Keiser | Blue Heron Consulting

This article was written for and featured in Animal Health News & Views.

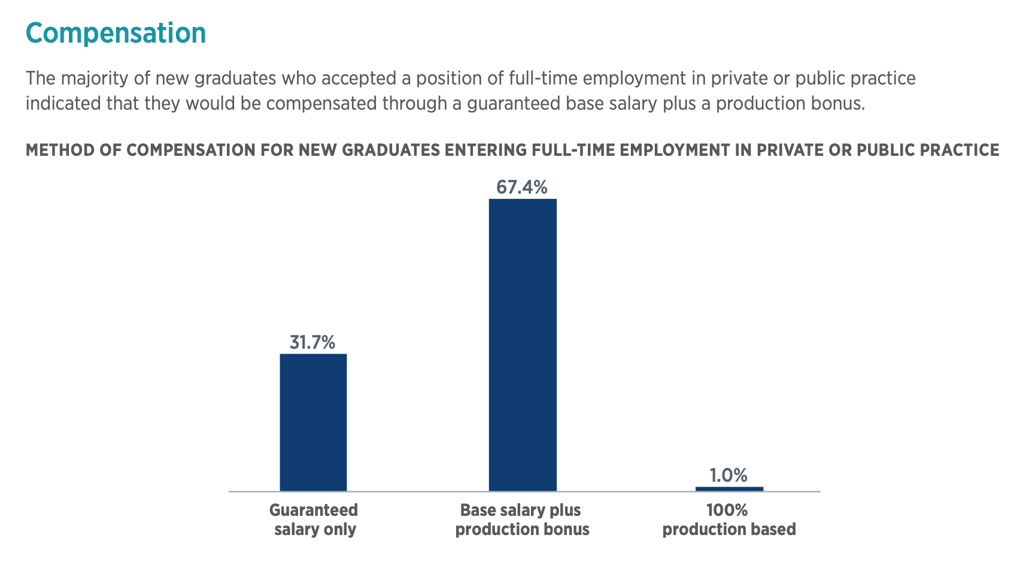

In a previous article, I elaborated on a topic (pros and cons of in-house charities) that was borne of questions I received in a professional skill’s class at a veterinary school where I was teaching. This blog has similar roots and as we head into new graduate hiring season, I’m getting more and more questions on associate compensation models, and associated advantages and disadvantages. To help frame the conversation, I want to share an image from the 2025 Economic State of the Veterinary Profession (see above), detailing the break-down of compensation models offered to 2024 veterinary graduates.

As the graph shows, the majority of veterinary graduates were offered some form of base salary plus production, with about 1/3 of graduates receiving an offer of base salary only, and about 1% receiving an offer of straight production. With that data in mind, let’s discuss advantages and disadvantages of each model.

Guaranteed Base Salary Only

I sometimes hear students say they prefer this model because in this model “I don’t have to worry about my production.” While this model has plenty of advantages, I’d like to clarify the perception around production not influencing a guaranteed base salary. While it’s accurate that month-to-month production doesn’t impact a guaranteed base salary, it’s inaccurate to assume that an associate has no responsibility to produce in order to earn their salary long-term. Given the business model of veterinary medicine, and the common breakdown of primary expense categories (total payroll, Cost of Goods Sold, rent/mortgage, etc) and the need to post at least some profit for reinvestment into the team, equipment, facilities and hopefully a return on investment for owners, most hospitals can’t afford to pay an associate more than 25% of their production between both salary and benefits. There is some wiggle room here based on the practice model, but generally speaking 25% is a maximum line owners try not to surpass because in doing so, and given the other expense categories, the average fairly low profit margin of hospitals is diminished even more. Within that 25% benchmark, most hospitals allocate 20-22% of production specifically to compensation. Why is this relevant? It’s relevant because whether you’re paid a guaranteed base salary, a base plus production, or straight production, if an associate fails to produce enough to cover their compensation for a long enough period of time, that “asset” of an associate, because a liability.

To put real numbers to this, let’s say that you have a guaranteed base salary of $100,000/year. Using the rule of thumb that an associate is paid 20% of production (or 5 times their base), an associate earning $100,000/year needs to produce at least $500,000/year. Divide that out across 12 months and that equates to roughly $41,666/month in production. With a guaranteed base salary, if you fall below that monthly target, you still get your base salary. If you exceed that monthly target, you still get that base salary. There is consistency and peace of mind for some veterinarians in knowing the aforementioned. So, does that mean you don’t ever have to pay attention to what you produce? No. If, at the end of the year you produced $400,000, instead of the $500,000 you needed to produce to cover your base, at practice owner will be left in a situation where they are overpaying you. In this scenario, your compensation alone (not counting benefits) was 25% of your production. What happens next will depend largely on the practice, why the associate hit the production they did, and could take into account a plan to help the associate produce enough to warrant their salary. Eventually, though, if an associate can’t produce enough to cover their salary with the desired margins, a guaranteed base could be decreased to more closely align with their actual production, or, in some cases, the associate could be terminated because they’re costing the business more than they’re making it.

I share this not to dismiss the upsides of a guaranteed base salary, nor to tout another model over it, but I think it’s important to understand that regardless of compensation model in practice, production will eventually come into play and I believe it’s both a practice owner’s and associate’s, responsibility to track this information so that “unpleasant” conversations can potentially be avoided.

Moving on, let’s review some general advantages and disadvantages to the guaranteed base pay model.

Advantages

- Financial Stability – A guaranteed salary provides consistency, making it easier to plan for living expenses, student loan payments, and other financial obligations.

- Reduced Pressure – Without production-based incentives, veterinarians can focus on patient care without the stress of meeting revenue targets. While this is true to some degree, please keep in mind what we discussed above.

- Predictable Work Environment – New graduates can concentrate on learning and developing their skills without the anxiety of fluctuating income.

- Encourages Work-Life Balance – Since earnings are not directly tied to production, there is less incentive to work extended hours or see an overwhelming number of cases.

Disadvantages

- Limited Earning Potential – Without production bonuses, veterinarians do not have the opportunity to increase their income based on their caseload or efficiency.

- Less Motivation for Efficiency – Since earnings are not tied to performance, there may be less incentive to maximize productivity.

- Potential Employer Hesitation – Some employers may hesitate to offer high base salaries to new graduates without a proven track record of production.

Base Salary Plus Production (ProSal)

The base plus production model, commonly known as ProSal, offers a guaranteed salary along with additional compensation based on revenue generated. Production is typically measured as a percentage of services and products the veterinarian sells (equal percent could be applied to both, or in some case of “split rate production,” a higher percent is applied to services, with a lower percent applied to product sales), and additional earnings are calculated once production surpasses a predetermined threshold. Before we dive into advantages and disadvantages, let’s explore some real numbers to help illustrate how this works.

Using the same numbers from our previous example, let’s say an associate is offered a ProSal model with a base of $100,000 + 20% production. To generate enough to cover the base component, the associate needs to produce $500,000/annually (same math as described above under base salary). Broken out over 12 months, that equates to roughly $41,666 in monthly production. Where ProSal starts to differ from a guaranteed base is what happens when an associate produces more, or less (see “Negative Accrual” below), than the monthly target. For example, if an associate produced $50,000 in a given month, let’s say February, they would receive 1/26 or 1/24 (depending on how the hospital does payroll) on their first paycheck in March. If there were 26 pay periods, the base pay per pay period would be $3846/pay period ($100,00 salary divided by 26 pay periods) For the second paycheck in March, they still receive their base salary of $3846. Where the advantage enters the equation is when that associate produces more than the $41,666. In the example, we’re using, the math for the second paycheck of March would likely (while most hospitals pay production monthly, some do it quarterly, semi-annually or annually) look like this:

- February Gross Individual Production (i.e. what the associate produced; only including money that was collected by the hospital and minus all discounts): $50,000

- Production Target to cover base salary: $41,666

- For the second paycheck of March, the associate would receive 20% of $50,000 ($10,000) minus their guaranteed base of $3846, for a total second paycheck of the month in the amount of $6154.

The above illustrates the potential additional earning capacity for an associate under the ProSal model. Let’s dig into additional advantages and disadvantages:

Advantages

- Financial Security with Upside Potential – Veterinarians receive a stable income with the opportunity to earn more based on performance.

- Motivation to Increase Revenue – Since earnings can rise with higher production, veterinarians have an incentive to be more efficient and proactive in case management.

- Balanced Risk and Reward – Employers mitigate financial risk while still offering the potential for higher earnings, making this an attractive option for both parties.

- Ideal for Skill Development – New graduates can gradually build their efficiency and confidence without the immediate pressure of straight production.

Disadvantages

- Complex Compensation Calculations – Production-based earnings depend on factors such as revenue percentage, cost of goods sold, and employer-set thresholds, which can sometimes be difficult to track.

- Possibility of Earning Only Base Salary – If a veterinarian does not generate enough revenue to exceed the production threshold, they will only receive their base pay, limiting potential earnings.

- Pressure to Perform – While the base salary provides a safety net, some veterinarians may still feel pressure to increase production, potentially leading to stress or ethical dilemmas in recommending services.

- Competition & Case Hoarding – I sometimes get asked if including production-based pay can lead to competition amongst doctors and/or case hoarding (certain doctors “claiming” the high-dollar cases) and the answer is, yes. This can happen and does happen. My rebuttal is that when that happens, it’s a leadership and culture problem, not a compensation model problem. These issues only arise when hospital leadership allows it.

- Negative Accrual – Is another potential downfall to ProSal. Not only contracts contain a clause around negative accrual (and I’m seeing it less and less as I review contracts), but it does exist. The premise behind negative accrual is that if an associate fails to produce enough in a given month to cover their guaranteed base, they’ll still receive their guaranteed base, but the deficit is applied against any future production bonuses.

Straight Production

Straight production compensation means a veterinarian earns a percentage of the revenue they generate, with no guaranteed salary. This percentage usually ranges between 18% and 25% of collected revenue.

Advantages

- High Earning Potential – Veterinarians who are efficient and manage a high caseload can significantly increase their earnings.

- Encourages Efficiency and Productivity – Since compensation is directly tied to production, veterinarians are motivated to optimize their schedules, enhance client communication, and recommend appropriate diagnostics and treatments.

- Employer Preference – Many employers favor straight production models since it eliminates financial risk on their part.

- Flexible Scheduling – With earnings based solely on production, veterinarians can tailor their schedules based on their income goals, potentially achieving a better work-life balance.

Disadvantages

- Financial Uncertainty – Earnings can fluctuate significantly based on client volume, appointment scheduling, seasonality, and even economic conditions.

- Pressure to Maximize Revenue – Veterinarians may feel compelled to take on more cases, work longer hours, or recommend more expensive treatments to ensure stable earnings.

- Difficult for New Graduates – Without an established client base, efficiency, or case-handling experience, new graduates may struggle to earn a sustainable income in their early career years.

- No Paid Time Off or Benefits – Since pay is based on revenue generated, time off or slow appointment days can significantly impact income, making it harder to maintain financial stability.

Choosing the Right Model as a New Graduate

When evaluating job offers, new veterinary graduates should consider their personal financial needs, career goals, and risk tolerance. Some key factors to weigh include:

- Student Loan Debt – If financial stability is a priority, a base salary or base plus production model may be more appropriate.

- Comfort with Risk – Those who are confident in their ability to generate revenue and prefer unlimited earning potential may be more suited to ProSal or straight production.

- Work-Life Balance Preferences – Veterinarians who prioritize predictable hours and reduced stress may favor a base salary model.

- Long-Term Career Goals – If the goal is to gain experience while gradually increasing income potential, ProSal can offer a good balance of stability and incentive.

Each compensation model has its own set of pros and cons, and no single structure is perfect for every new graduate. While a base salary provides security, it may limit earnings; straight production offers high potential but comes with risk; and base plus production can provide a balanced approach. By carefully assessing financial needs, career aspirations, and work-life balance preferences, new veterinarians can make an informed decision that supports their professional growth and long-term success.